Detroit Free Press

2/1/1970

The Berkeley rebels five years later

Michael Maidenberg and Philip Meyer

(Seven-part series, Feb. 1-7, based on survey of 230 FSM participants.)

Five years ago, today’s youth activism movement was born in the Free Speech Movement confrontations at the University of California Berkeley campus. In a landmark survey seeking to determine the long-term direction of young radicalism, Free Press reporters Philip Meyer and Michael Maidenberg located more than 400 of the Berkeley rebels and 230 of them completed detailed questionnaires. Thirteen were interviewed at length. From comprehensive analysis of the responses and the interviews, the Free Press team has written a special seven-part series.

The young men and women who began the student rebellion five years ago in Berkeley, Cal., are older and wiser now. But for the most part ago has not made them feel less radical.

This finding, based on a six-month search for the rank-and-file Berkeley rebels of five years ago, contradicts a hope cherished by much of the older generation. The youth movement is not a passing fling by over-active children. Its effects linger when their childhood is gone.

The searched turned up the addresses of about two-thirds of the more-than-600 University of California students who were arrested in December, 1964, for occupying Sproul Hall. Half of those contacted—230—completed questionnaires about their attitudes then and now.

A small, randomly selected cross-section was interviewed in person. The purpose was not to find out what the former leaders are doing, but what the vastly greater number of followers is doing today.

Among the findings:

● In self-addressed radicalism, the group as a whole has changed hardly at all. But while radical thought has not diminished, radical activity has.

● The overwhelming majority—90 percent—supports more recent campus disruptions which sprang from the Berkeley example, even though these have involved tactics that were more violent and issue which were less clear.

● Eighty-four percent, knowing the consequences of getting arrested and having accumulated the wisdom of five more years, would do it all again.

● Their views about the trustworthiness and concern of the American government for its citizens differ radically from those of the nation as a whole. Some 63 percent of a national survey trusts the government “just about always” or most of the time; only five percent of the Knight Newspaper sample agreed.

● The student revolt is not explained by a “generation gap.” Radical students tended to have radical parents. The few who withdrew from radicalism in later years tended to have parents who disapproved of their involvement in the first place.

THE BERKELEY Free Speech Movement (FSM) was a loose coalition of students. Their central issue was the right of students to continue a custom of distributing political literature along a 26-foot strip of brick walkway at the entrance to the campus.

It reached its climax on Dec. 2, 1964, when demonstrators packed Sproul Hall, the administration building, to protest university action against FSM leaders. A total of 814 persons, including some 200 non-residents, were arrested.

Since then, some of the leaders have achieved greater notoriety. There was Jerry Rubin, who graduated to Yippiedom and appeared at a congressional hearing in an Uncle Sam suit. He is one of the “Chicago Seven” defendants in the conspiracy trial which arose from the violence during the 1968 Democratic convention.

But for the few flamboyant leaders like Jerry Rubin there were many followers like Janie Nielsen: Quiet, soft-spoken, out of the public eye. While working as a letter sorter in the Berkeley post-office, to earn enough money to go back to school, she organized a new union for the post office. The union is now looking into problems of discrimination and patronage.

“Since FSM I’ve become more radical, really,” she says. “Then I had some qualms about sitting in as a means of demonstrating. Now my only problem is with violence, would I be aligning myself with it or not. I would condone it but I don’t know if I would be there.

When the Berkeley rebels in the survey compare their political feelings of today with how they felt in January, 1965, just after FSM, here is what happens:

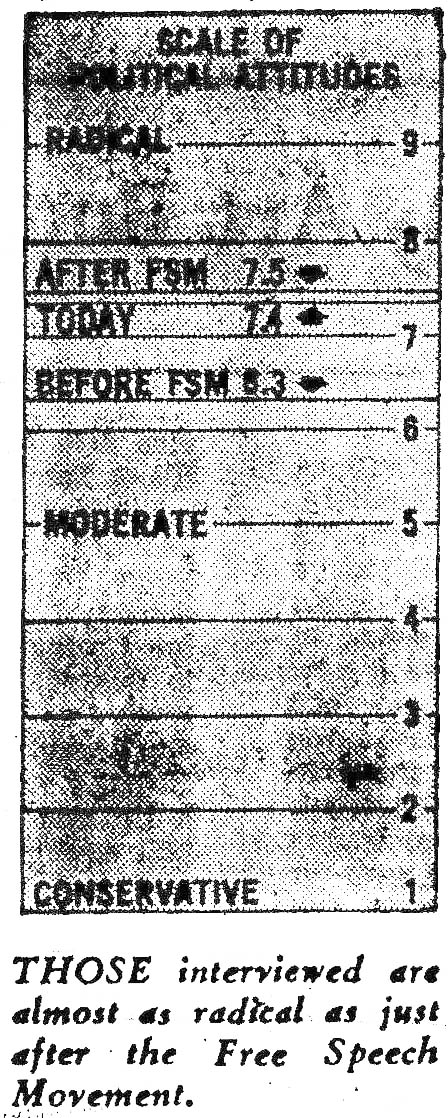

The questionnaire included a numbered diagram to represent the political spectrum, with the most radical position marked “9” and the most conservative position marked “1.” The respondents were asked to tell where they would place themselves on the scale at three different points in time: Before the Free Speech Movement, immediately after the arrests, and “today.”

Thinking back to the days before FSM, the participants gave themselves an average radicalism score of 6.3. Immediately after FSM, the average jumped to 7.5. Most important of all, the average for today shows no significant change from five years ago. It is 7.4.

About 70 percent said they were more radical after FSM than before, and of those who had not gained, most were fairly radical to begin with.

For some, the focus of radical feelings has changed as old issues and groups died out and new ones took their place.

TAKE KAREN HOROWITZ. She lives in a small eastern state where her husband, who was also arrested during FSM, works as a theoretical physicist. He works for a major corporation and she takes care of two children in the pleasant, but not typical suburb where they live.

They have marched in all the anti-war demonstrations. She has picketed the local draft board.

“I offered to sell the Black Panther newspaper in the suburbs,” Karen recalls. “Not that it’s going to convince anybody, but because the suburbs don’t know anything about anything. They don’t know what’s happening.”

She calls herself a “pluralist.” Meaning what? “The NAACP and the Americans for Democratic Action should stay around. I don’t even think they should change their images much.”

For her, there is no return to the liberalism of an earlier generation:

“The liberal view to me was a nice man sitting behind a desk who would say yes if you asked him nice enough. That’s not true. There is violence and there is a very strong determination against all the things the liberals thought there wasn’t. If you don’t recognize this, you’re dumb or dishonest.”

Her scorn for “niceness” is echoed a continent away by Len Farbstein. Farbstein is trained as an engineer but has been working as business manager for an underground newspaper in Berkeley.

Farbstein makes this analysis of the current Berkeley administration:

“The people in there now are tactical people and they’ll do anything if they think they can get away with it. The only thing that can stop them is force or the threat of force. FSM was a demonstration of moral witness since there was no real tactical objective to be achieved in Sproul Hall. But I’m not so hot on moral witness any more.

“Since the opposition has sort of wised up, we’ve run out of pillows to punch. Things are tougher and as a result we have to use tougher tactics. Nothing else will work.”

Farbstein admits that he was “radicalized” by FSM. Others are cautious in their definitions.

“You mean, like, my eyes had been opened? That kind of thing? asks Diana Wheeler, who is now working toward her PhD in political science at Berkeley.

That would be hard to say. It changed me in the sense that there was an excitement about it that was very warm, a lot of comradeship. In that sense it made political activity very positive looking.”

In contrast to more recent student disturbances, the confrontation that resulted from the Free Speech Movement developed with apparently little planning.

FSM INVOLVED more students, and probably a wider variety of students, than other campus clashes of the 1960s. Most of the 224 non-students of the 814 arrested in the Sproul Hall sit-in were ex-students or the wives of students.

Although FSM took the radical step of confronting Berkeley administration, the issues involved did not call the university and the surrounding community. FSM was therefore able to attract a great number of middle-ground students, although the leadership remained in the hands of student radicals.

The administration underestimated the ability of students to organize and gain support of their position.

FSM came at the end of the Johnson-Goldwater presidential campaign, which had stirred political activity on the campus. The autumn of FSM followed a summer of civil rights work in the deep south, and several FSM leaders returned to campus with this fresh in their minds.

The Free Speech Movement began on Sept. 16, 1964, when the Berkeley administration announced that students could no longer set up tables near the main campus entrance for use in advocating political action and collecting money for causes.

FSM leaders later attributed this sudden action, to political pressure by former Sen. William Knowland, whose newspaper, The Oakland Tribune, had just been picketed by a group who organized themselves near the tables.

In response, the President of the University of California, Clark Kerr, described the ban as a routine bureaucratic move which “underestimated the intensity of student reaction.” The administration was caught off-guard.

The whole student political spectrum from Young Socialists to Goldwater for President

Turn to Page 4B, Column 3

(Continued from Page 1

supporters protested. Negotiations began between students and administration.

Student unity did not last long as differences over tactics arose. Members of SNCC, the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee, and CORE, the Congress for Racial Equality, decided to test the nab by setting up tables.

On Oct. 1, a university policeman attempted to arrest a student manning the CORE table. A police car came to take him away, but a crowd sat down around the car and prevented it from moving.

This was the start of a two-day incident, which attracted at its peak an estimated crowd of 5,000 persons. The Berkeley protest escalated.

The escalation attracted Tom Edelman, and the story of how he was swept into FSM is a classic example of “radicalization.”

He was on his way to a rally at Sproul Hall when he came upon the surrounded police car. Surprised and upset, he decided to cut classes and join the crowd around the car.

Earlier Mario Savio had taken off his shoes and climbed politely on top of the car to make a speech.

“There is a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part; you can’t even tactily (sic) take part, and you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus and you’ve got to make it stop,” Mario Savio told FSM members.

“I got hit with an egg,” Edelman remembers, “and I decided, this is ridiculous, I’m not going to let him get arrested. So I left, changed clothes, and came back. I wanted just to listen, but I didn’t like the antagonizing.

“I was right up against the car. It became a very emotional thing. There was a lot of people singing and there was a lot of spirit. I really felt I had a lot to say, and I understood what people were saying.

“The girl next to me was a really beautiful girl. She was black, which I guess at that time gave me a real emotional thing. We had our arms locked, we were sitting together at the car, we were singing—it was very emotional.”

Five years later Edelman can dispassionately analyze those powerful feelings:

“All that emotion fostered the commitment. I don’t like to emphasize this because intellectually I think I agreed with what was happening. But when you have two sides set up, the emotionalism becomes the real strong thing which commits you.”

The real common denominator was being arrested. Cathy Brown was arrested.

“I was really terrified at the time,” she recalls. She was then a teaching assistant and at 26 was far older than most demonstrators.

I looked at these girls around me, who were two to six years younger, and they were just joking to each other about the last time they had been arrested in Bogalusa, or wherever. They had been to the south and were not the least bit frightened.”

Karen Horowitz remembers the scene:

“They took a student and they put his hands behind his back and they said viciously, Crawl! Crawl! Crawl! In my van, the driver was calling us bitches and whores. We really got an insight into blacks and Nazi Germany.”

AFTER THE police car incident came compromise, new protest, new rules that would have met the demands of most protesting students, and disciplinary action against leaders of FSM. Outraged, FSM demanded that these charges be dropped. The administration refused. All spirit of compromise vanished.

The sit-in and the arrests led to a torrent of self-examination by individuals and committees at Berkeley. While the committees met in slow deliberation, FSM leaders tried to keep their organization alive. But the issue had spent itself, and within a few months, FSM as a strong student force was dead.

The 800 individuals who had been swept together in the sit-in now began to move their separate ways.

Diana Wheeler, who hated groups and meetings and thought herself very lazy, joined CORE.

“I had been interested in civil rights prior to FSM, but the fact that I met people I liked in FSM who were in CORE made it more positive to go to those meetings. We had a big campaign against restaurants in Oakland that spring.”

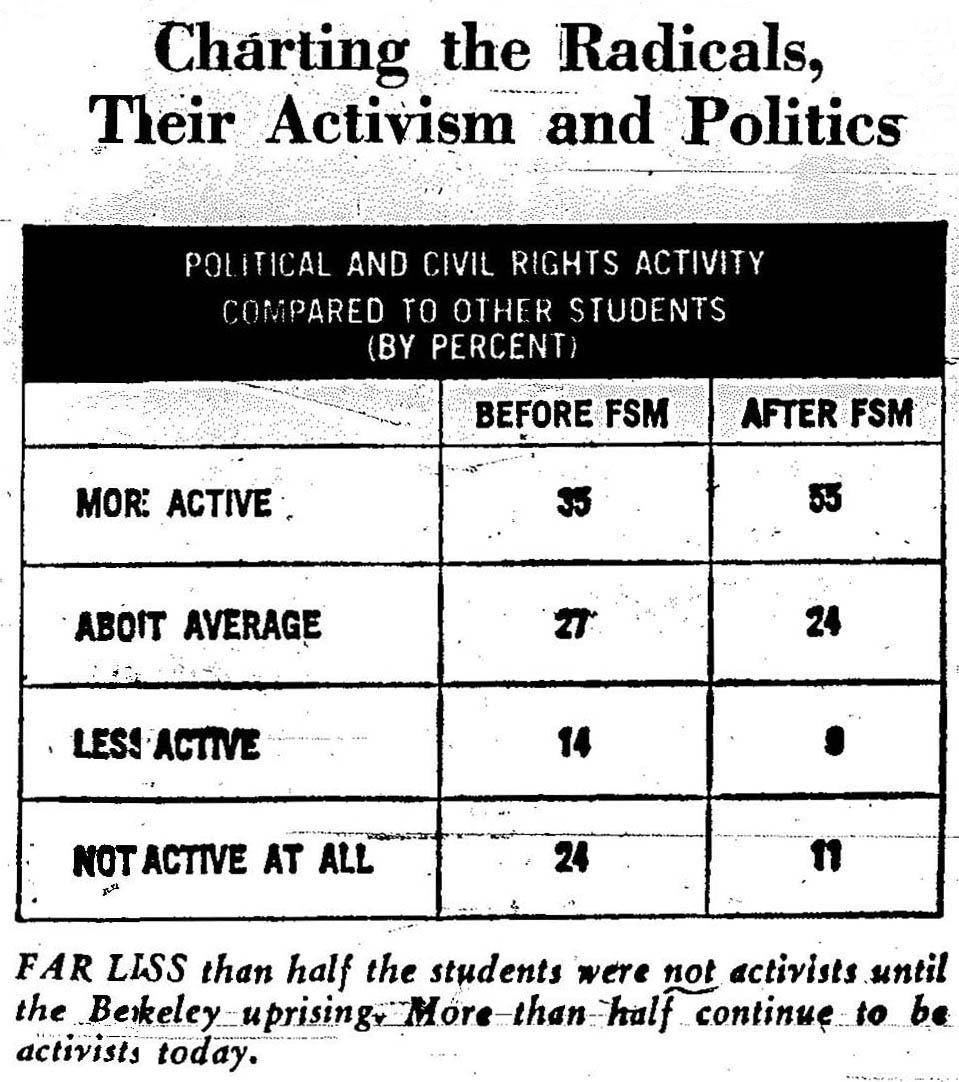

Participation in FSM led to a general sharp rise in civil rights and political activity, particularly as the Vietnam war grew.

Of those surveyed 55 percent said they were more active than other students in political and civil rights organizations after FSM. Only 35 percent felt they were more active before FSM.

And as they look back on it now, 54 percent feel the sit-in was “appropriate and effective” as a technique for achieving reform, while 36 percent feel it was appropriate but not effective. Only 9 percent now consider the sit-in a poor tactic.

If it was theirs to do over again, 84 percent would join the sit-in. Some 10 percent said they would not join but express support. Only two percent would oppose the sit-in.

“Of course I’d do it all over again. No doubt about it,” said one. “To my mind that (FSM) was a very pure kind of goal, something everybody should be for.”

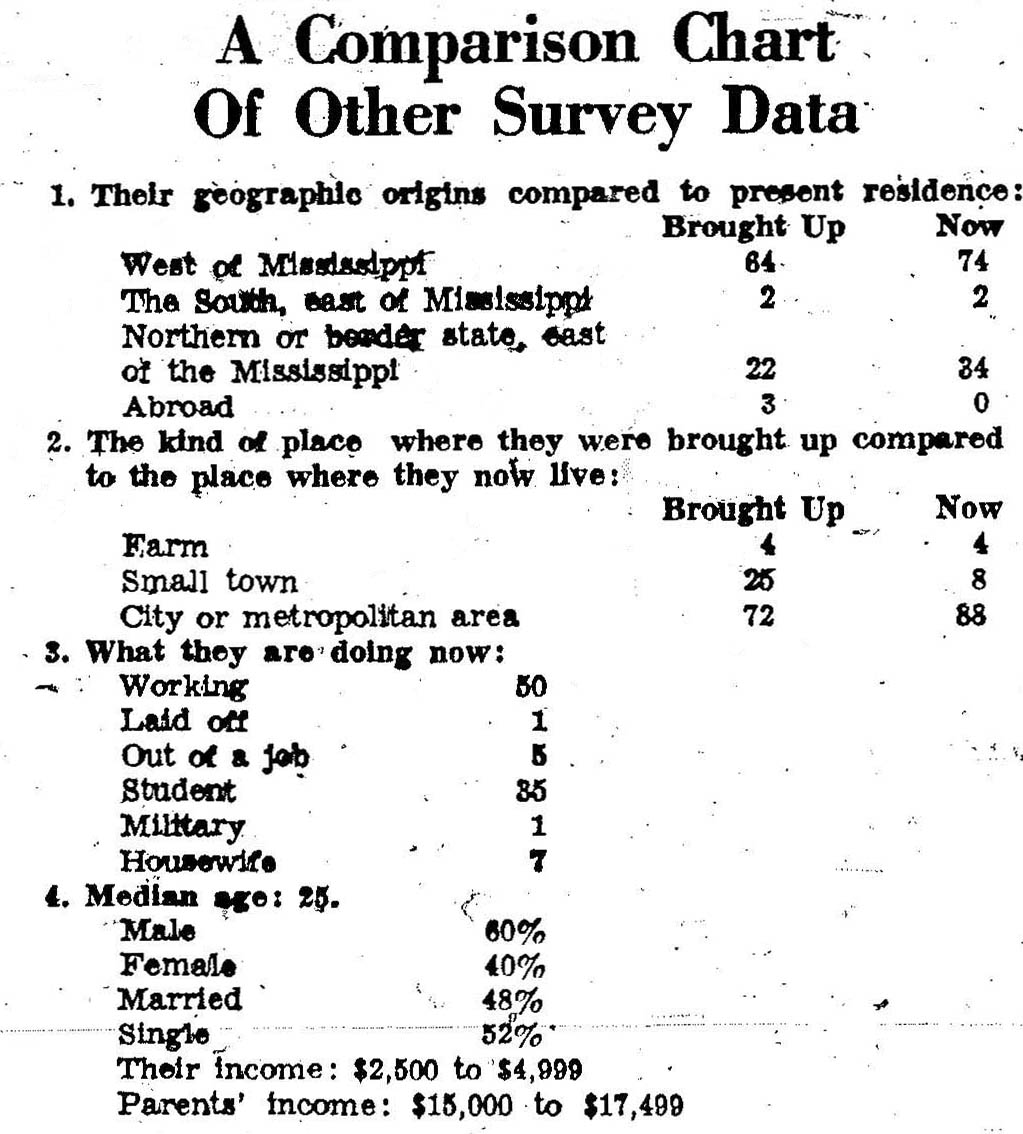

Today the Berkeley rebels live mostly in cities or metropolitan areas (88 percent), about half are working, 35 percent are still students and 7 percent are housewives. Of those working, 27 percent are teaching, 13 percent are in social work and 10 percent are doing clerical work of one kind or another.

They have tended to stay in the west: 64 percent were brought up west of the Mississippi, but 74 percent live there now.

Many have gravitated to the San Francisco-Berkeley area. They just can’t tear themselves away.

JANET ROPER is from a small town in northern California but she has stayed in Berkeley, and works as a social worker in a nearby city.

“It’s incredible to me,” she says, “how Berkeley can support all the graduates of the university because everyone I know who’s gone to school here stays. It’s sort of an ideal place to live. Very tolerant. Beautiful climate. Just basically a groovy place to be.”

Through five years of tumultuous politics and personal development—marriage, divorce, children, graduate school, experimentation with drugs—the Berkeley rebels have maintained their radical attitudes.

If the fact of growing older were to push them toward more conservative attitudes, it ought to show by now. It does not—except for a minority facing special pressures such as disapproving parents or religious conflicts.

Behavior, of course, is a different story. A 25-year-old has less time and opportunity for radical politics than a 20-year-old. But on the kinds of political behavior that are easy to partake in—such as voting—the radical attitudes take hold.

Nobody voted for Nixon and only a moderate minority voted for Humphrey. Many could not bring themselves to take part in this traditional political process at all. And those who are not still active in protest tend to look with approval at those who are.

Fred Miller is 24 today, married, and a father. He spend two years in the Peace Corps in South America. He is working, but he plans to go back to school for a doctorate in clinical psychology.”

He is against violence because “you don’t build a humanist society using inhuman tactics.”

But he adds:

“The protests and the demonstrations should be kept up. They are good things. The hard, bitter reality is that if we ever do get out of Vietnam, it will be because of the unrest that’s been created in this country, not because of a re-examination of basic principles. This should be very clear by now.”

MONDAY: The few back-sliders.

Sidebars

13 Berkeley Rebels Today: A Special Look

The Free Speech Movement and the Sproul Hall sit-in are history now. The events are frozen in the past, the actors are rigid in their postures, like figures in old photographs.

For those arrested that oddly cold night in December of 1964 the sit-in was only a flash, an instant in their lives when they found themselves a part of history.

Seven men and six women were picked at random from those who were there, and were asked to recall their experiences at length. All were interviewed between last Nov. 18 and Dec. 5.

Their lives all intertwined that one night, yet each of the 13 has his own perspective on what happened then and what has happened since.

Their real names are not used; but even if they were they would not be recognized as the "leaders" or the "spokesmen" in the·Free Speech Movement. They were distinguishable from the thousands of other Berkeley students only because they, for the first time in their lives, were arrested.

|

CATHY BROWN: She is 31 and expecting her first child. She and her husband, a professor of history, live in the hills above Berkeley. She is completing her dissertation in English literature. She was active in and anti-draft group, but the current student movement upsets her. “When I look back at the FSM, it’s another world, so sweetly old fashioned.” |

|

LINDA CARTIER: She and her husband, who is working temporarily as a bus driver, are trying to simplify their lives : They have given up smoking and· rich foods; their San Francisco apartment is sparse. She is 24 and expecting a child.·Neither she nor her husband is, politically active. "I think that :people have to go inward rather than ·outward.” |

|

ARTHUR COKER: At 24,·an accomplished classical guitarist who lives alone in Berkeley. He earns his living playing concerts and teaching guitar. Although he has been active in several Berkeley events, most recently "People's Park," Coker refuses to classify himself. "Each person by the way he lives and everything he does--that is his politics.” |

|

TOM EDELMAN: Hard-driving and self-confident, Edelman, 24, is finishing his doctorate in clinical psychology at UCLA. After FSM he went through a drug stage, but now runs a drug abuse program and has testified before a Congressional committee. Deep involvement in politics is past for him. “I always knew what I wanted to do and I always got really deeply involved in it, experienced it and left.” |

|

LEN FARBSTEIN: He lives and works at being a radical. Farbstein, 25, is a talented engineer and worked as a business manager of an underground newspaper. He is precise and coldly serious; his radicalism has steadily increased. “I’m waiting for the time when we are going to start analyzing the establishment’s responses and attempting to manipulate those responses for our benefit.” |

|

MILTON GOLDSTEIN: He is a professor of architecture and deeply involved in his work. He teaches in Seattle but keeps close ties with Berkeley. Goldstein, 26, has a greater devotion to design than to any political movement. “I don’t have a vision like I used to of a new society being born out of this kind of activity.” |

|

RICHARD GOODMAN: Goodman was a leader of FSM, but in the five yearsTurn to Page 4B, Col. 1 following has gone through many difficult 'changes: a divorce, drugs, Eastern, religions. Last year he immersed himself in transendental meditation, traveling to India to study under the teacher of the Beatles: Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. "I feel I have transcended worldly politics.” |

|

KAREN HOROWITZ: Two children and a secluded suburban environment have not dampened her radicalism. Her husband is a theoretical physicist who works for a large corporation in the East. Both were arrested during FSM and both have sought ways to remain active. She marched in Washington and picketed the local draft board. “More radical things remain to be done among women, particularly in the suburbs.” |

|

FRED MILLER: Miller, 24, went into the Peace Corps in South America following his graduation in 1966. He and his wife and child now live in New York, where he works with an experimental education firm. The Peace Corps mellowed him, but not completely. “I believe in maintaining a radical position, but not precluding the possibility of coalition with liberal groups on specific issues.” |

|

JOHN MILVIO: Milvio, 24, has short hair and a freewheeling, independent personality. He is in Berkeley working as a warehouseman, trying to decide on a career. FSM forced out a political side of him that he hadn’t realized existed, but he finds much lacking in recent student and New Left politics. "If I'm going to participate in your revolution, you have to show me something that's going to be gained from it over a long period of time." |

|

JANE NIELSEN: She is 27, was married and divorced and for the last year has worked at the Berkeley post office as a letter sorter. She hopes to get a Master's and teach. She is disturbed about violence, but thinks it is inevitable. Although she is less active than five years ago, she feels her attitudes have gone the other way. "I'm probably more radical, but on the other hand, so is the world. |

|

JANET ROPER: Since her graduation she has been a social worker in the bay area, and her work and her own life have occupied her. She is 26, and feels she is just now beginning to emerge from political inactivity. But she feels older, and has more to lose. “To put my job on the line, which to me is doing something, is a hell of a lot harder decision for me now than when I was a student.” |

|

DIANA WHEELER: Diana is 25 and has an air of weariness about her. She and her husband, a sailor who had not been to college when she met him, and their baby live near Berkeley in Oakland. She is studying for a PhD in political science. She is no longer politically active, and most current politics depresses her. “People who are still active just amaze me.” |